To begin with, let’s dive into the history of notion ‘portfolio investments’ and figure out the difference between portfolio investments and other strategies of investing. Before entering the markets with the purpose of investing, one has to choose the type of investments he is going to work with.

There are three main options of investing, i. e. three basic strategies of behaviour in financial markets that are available to any small private investor. These strategies are listed in historical order of approaches’ emerging, the approximate time of approaches’ emerging stated in parenthesis.

Theoretical basis – technical analysis, time of emergence – the 1980s.

Theoretical basis – fundamental analysis, time of emergence – 1930s – 1940s.

Theoretical basis – Asset Allocation, time of emergence – 1980s – 1990s.

(I should note, that there are also other strategies of getting revenues in financial markets, which usually are not available to a small investor not having a significant amount of capital and/or institutionalization of his activity: brokering and dealer activity, underwriting, M&A activity, arbitrage and so on. In this series of articles, we are not going to address these approaches).

Further, we are going to address the features of all three approaches and talk about the reasons why they emerged exactly in this order as well as how financial markets changed in this leading to shifting in the investors’ priorities.

Unfortunately, there is one more group, in reality, moreover, it is almost larger than the three previous added together. It includes players, ‘noobs’, unprofessional investors, the people who do not really understand what they are doing in markets and try mixing all the above-mentioned strategies. It is not recommended to do so.

Usually, most of the failures in the stock market happen because people do not understand what type of investing and what type of behaviour in financial markets, they are trying to make money with.

One can be a successful speculator. One can be a successful active investor. One can be a successful passive investor. But when one starts to try, let’s say, investing, bearing the market and after losing some money begins to think of himself as a long-term investor or, on the contrary, when one decides to invest with long-term view but at the same time withdraws from the strategy on stop-loss orders, in this case, typically, one is going to fail.

So, there are three main ways of investor’s behaviour in the financial markets. Let’s address them in detail, paying attention to historical conditions when the theoretical basis for these concepts was emerging.

“Investing should be more like watching paint dry or watching grass grow. If you want excitement, take $800 and go to Las Vegas.” – Paul Samuelson

Let’s begin with speculations, that appeared first of all. It is clear, that speculations existed, probably, forever, since the dawn of humankind and financial markets, but they tried to put some theoretical framework for them at the end of the 19th century for the first time and these efforts are associated with the name of Charles Dow who is considered to be the founder of technical analysis in the Western world (Europe and the USA). This is the Daw who invented the Dow Jones Industrial Average. And in the 1890s, he first drew up the basic tenets of technical analysis, and also described various behaviour patterns of graphs, patterns, etc.

What, in fact, does technical analysis? Perhaps for someone, it will be a revelation, perhaps for someone, it is not news, but technical analysis is an attempt to play against the mass of non-professional players based on the human and psychology factors. So, it turns out that when people react together in a crowd, heap, group on the same stimuli, they are prone to collective irrational (often unprofitable for themselves) actions. For example, either all together fall into euphoria and drive quotes to the heavens, or, on the contrary, panic and start selling assets cheaper than they really cost.

Charles Dow first tried to analyse price and volume charts and gave practical advice, in fact, advice to speculators, on how to try making money on short-term price fluctuations.

Does technical analysis work? Does the approach of Charles Dow work? The correct answer is this: they probably worked well at the time when Charles Dow lived when traders did not have computers, when information reached people with different levels of delay, when the main signals about stock prices were perceived at best from telegraph tape or ticker. In this case, when some people (an obvious minority) drew charts, and other people (the majority) did not do this, falling into euphoria or vice versa in a panic together with a market crowd, Charles Dow’s approaches, perhaps, really helped individual market participants to derive additional benefits from it, using the ideas of technical analysis.

Is it possible now, in the age of personal computers, when information simultaneously reaches all market participants, and everyone simultaneously observes the same graphics on the screen? Further, I am going to explain to what extent technical analysis can be useful in the present circumstances, but for now, let’s consider the following approach.

The second popular approach is active investment, the theoretical basis for which is fundamental analysis. It is appeared in the 1930s – 1940s, and is usually associated with the name of Benjamin Graham, as well as with the name of his perhaps most famous student – Warren Buffett, who skilfully applied these methods and as a result of the implementation of these approaches deserved receiving the status of the most famous and wealthy investor in the world.

Fundamental analysis is based on an analysis of the financial condition of the business behind the shares. The subject of the study is the financial condition of the company, which is being researched, first of all, based on various balance and reporting information, as well as based on other information about the issuer’s business.

As in the previous case, Graham’s approaches probably worked fine in the days of Graham. At the same time, it is necessary to understand that in Graham’s time, to obtain the necessary report, it was necessary to shake in the train halfway across the country, meet with the company’s management or bribe the secretary with dinner, come back with a pile of reports, and then carefully analyse them. And this, indeed, gave one serious advantage compared to those who did not see these reports and did not analyse them.

In our century, when all reports are published on the Internet in digital form, and almost instantly become available to all market participants, the question of whether you will have an advantage, possessing some information that others do not know, causes more and more doubts. Concerning the question to what extent fundamental analysis helps to beat the market, I am going to try to give an answer further, but for now let’s consider the last, most modern method of investment.

Finally, the third group, the third approach to investment, which we are going to talk about today, is passive investment. On the one hand, they are often very fairly associated with the name of the American economist Harry Markowitz, the founder of portfolio theory, who wrote the article ‘Portfolio Selection’ in 1952, and on which all modern principles of passive investment are based.

However, the portfolio investment approaches themselves became widespread not in the 1950s, but much later, in a slightly modified form called Asset Allocation approximately in 1980 – 1990s, that is, only 20-30 years ago. Active implementation of new approaches turned out to be possible for several reasons.

Firstly, personal computers appeared and massive distribution of them began, allowing to process large volumes of statistical data.

Today, the use of portfolio approaches does not cause major technical difficulties; to confirm these hypotheses, the ability to work with spreadsheets like the usual Excel is sufficient. But in the 1950s, there was no Excel, no technology on which it could be launched. As a result, for a very long time, for several decades, Markowitz’s approaches were not in demand, and he received the Nobel Prize for them (in fact, for the article of 1952) only in 1990. Markowitz himself, by the way, admitted that the happiest day of his life was not the day he won the Nobel Prize, but one of the days of the 1970s, when he managed to get access to the mainframe computer to test his theory by computer modelling, and to make sure that his theoretical calculations were correct (for the record: the price of launching a task on such a machine was then at a cost comparable to the price of a new car).

Secondly, for the mass implementation of passive investment approaches, suitable investment instruments were required.

In particular, index funds have become one of the most important tools for passive investments. The first index fund was created by company Vanguard under the leadership of John Bogle in 1975 and, in fact, revolutionized the market of financial services. Before the emergence of index funds, managers took unreasonably high commissions for their work, which in most cases were absolutely unjustifiable by their results (according to statistics, up to 80-90% of managers over long periods of time lose to market indices). The emergence and active implementation of index funds has made it possible to invest in extraordinarily wide markets, pay minimal management fees (management in this case, is passive, and therefore does not require professionals with high salaries), and not to take the risks of managers ( risks that managers will manage your money worse than the market).

As a result of these technological changes, the ideas of passive investments began to gain popularity in the States and Europe in the 80s-90s. They were quickly adopted by the largest and world-famous investment companies. On the webinars, I present examples of portfolio approaches from companies such as Fidelity, Vanguard, Merrill Lynch, T. Rowe Price, Morningstar, AIG, Oppenheimer Funds and other recognized professionals of the modern investment market.

However, it is interesting that while applying these approaches for the VIP audience, for wealthy investors, companies did not rush to propagate passive investment approaches to the general public actively (with the exception, perhaps, of Vanguard, whose head, John Bogle, contributed a lot to promotion passive approaches). Why? Because attempts to actively implement the ideas of passive investment lead to lower profits for the companies themselves. It is much more profitable for companies that you either try to trade independently or donate money to active trust management, to active mutual investment funds. And so, the company made money on you.

What is the nature of portfolio investment strategies? First, think about the answers to the following questions:

The first question (about the choice of the moment for the purchase of assets) is to determine the supporters of market timing (and, probably, technical analysis). You will answer ‘yes’ to this question, if you think that it is possible to determine when, for example, it is better to buy Gazprom shares, or, say, gold – now or later? And maybe it’s time to sell or short?

The second question (about choosing the best securities for investment) is for supporters of fundamental analysis. Answering this question with a ‘yes’, you assume that it is possible to decide that next year Microsoft, for example, will be more profitable than Exxon (or vice versa). Or that the preferred shares of Exxon will be more profitable than ordinary Exxon shares, considering not only dividends but also exchange rate fluctuations?

What are your answers to the mentioned-above two questions – “yes” or “no”?

Asset Allocation implies a ‘no’ answer to both of the questions. The portfolio investor deliberately refuses both attempts to predict the best moments for entering the market (which means do market timing) and to choose individual securities that may bring maximum profitability in the future.

How have ideas with about ways of making money in financial markets transformed over time? How and why did the prevailing ideas of the market people change from speculation at the beginning of the last century to active investments in the middle and passive investments at the end of the 20th century? What changed meanwhile?

The short answer is that the markets themselves and the environment around them have changed. A more detailed answer to the question is related to the hypothesis of an effective market. It is often criticized, but criticism is usually associated with a misunderstanding of the statement’s substance. The market efficiency hypothesis is an abstraction, a theoretical or even a hypothetical construction, and a fully efficient market is something like never intersecting parallel lines from Euclidean geometry or a “Spherical Cow” from the famous fundamental physics anecdote.

The main idea of the market efficiency hypothesis is as follows:

The market is considered effective conserning any information if this information is immediately and fully reflected in the prices of the asset.

The conclusion of this hypothesis is that market efficiency makes the information useless for making super-profits. The current prices of all assets are always fair and change only under the influence of new information. In an efficient market, only short-term random speculative profits are possible. In an efficient market, it is impossible to obtain speculative profits on an ongoing basis in the long term.

I will try to explain it with an example. Imagine you have some information that other people do not know, and you know how to make money from it. Let’s say you regularly collect mushrooms in the forest near your villa and sell them on the market and you consider your way of earning as reliable and practically risk-free. This approach will only work until 10-100-1000 or more of people like you appear on the same market, who also learn about this strategy and also begin to apply it. As soon as this happens, your approaches become useless, because people doing the same thing as you instantly equalize market prices, making such information not unique, but well known. A herd of mushroom pickers tramples down your mushroom glade very quickly, and the additional supply of mushrooms on the market lowers their prices.

Pay attention: no one claims that you can no longer find mushrooms. The thing is that you will not be able to consistently make money collecting mushrooms. Similarly, the hypothesis of an effective market does not deny the possibility of a random win on the market. But according to it, you can’t do it systematically. Your result will be close to random. Today we win, tomorrow we lose.

There are three degrees of market efficiency:

when the price of assets fully reflects any past information about it. For example, when people simultaneously see on the screens the same graphs, the same figures build on these graphs, support-resistance levels or some other more complex patterns such as Elliott waves or Bollinger bands. As a result, making a deal, these numerous people instantly lead the market to the state in which technical analysis ceases to produce results.

The consequence of a weak form of market efficiency is that technical analysis is useless.

when the price reflects all the information: both past and public, and internal. In this case, even inside information becomes useless. This is an ideal market condition in which any information, including some inside information, instantly becomes known to the entire market.

The consequence of a strong degree of market efficiency is that insider information is useless.

With the development of financial markets, their efficiency is increasing. With the improvement of technology, communications, market analysis tools, the legislative base, with an increase in the number of players in the markets, markets consistently go through stages of growth – from inefficient markets to markets with a weak, medium, and then a strong degree of efficiency. At the same time, a fully efficient market (as well as non-intersecting parallel straight lines, as well as a ‘Spherical Cow‘, apparently, remains unattainable in practice, but it can approach this state very closely.

This is a theory. And what does it have to do with life? What are the real markets – in America, Russia, and other countries? What efficiency do they have?

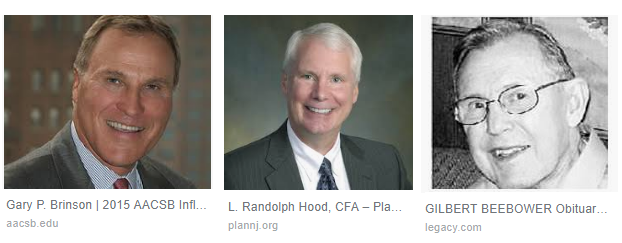

In 1986, three American scientists – Gary Brinson, Randolph Hood, and Gilbert Beebower – tried to answer this question by conducting a study of the real American market, or rather, the results of asset management on it.

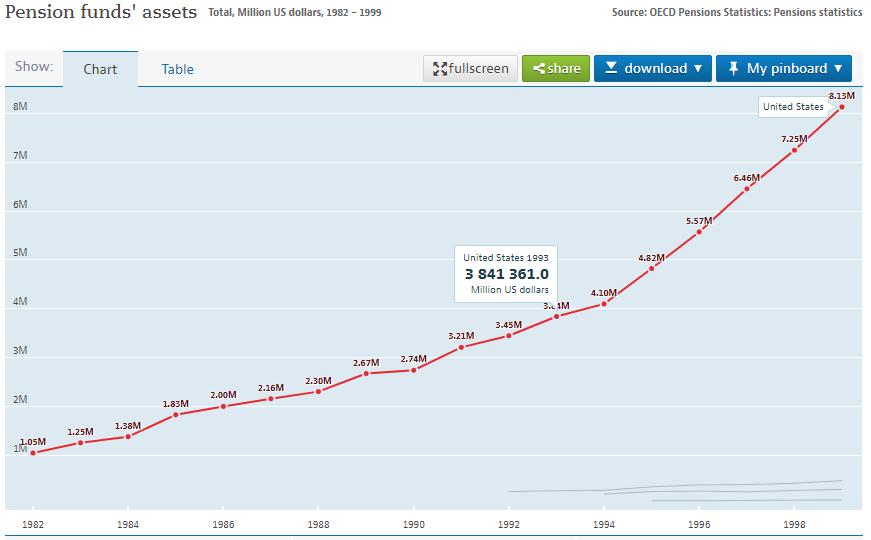

They had detailed data on activities in 91 large American pension funds with assets ranging from $ 100 million to $ 3 billion in the ten-year period ending in 1983. Moreover, the database contained not only the results but also information on how exactly these operations were used to obtain these results. It should be emphasized that we are talking about the largest funds that could spend huge money on salaries of the most talented managers and analysts and access to any information and any market research.

To investigate the reasons that affect the profitability of management, American scientists applied regression analysis – a mathematical method that allows evaluating the influence (or lack of influence) of individual factors on the final result. The results of their work were presented in the article ‘Determinations of Portfolio Performance’, published in the ‘Financial Analysts Journal’ in 1986.

The results of the study were shocking to Wall Street.

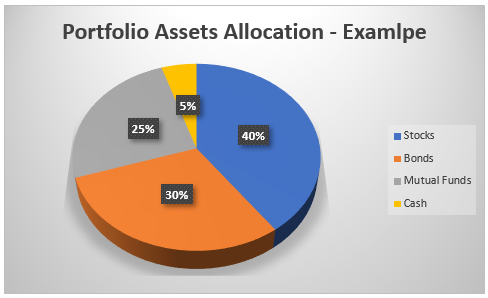

The degree of influence of various factors on the results of investments was as follows:

At 94%, the performance of the funds was determined by the correct distribution of assets, the choice of the percentage of broad classes of assets — stocks, bonds, and money market assets — in the investment portfolio. Only 4% of the funds’ returns was determined by the choice of specific stocks, that is, what fans of fundamental analysis including Buffett are doing. And only 2% of success (or failure) was made out of the timing of the correct or incorrect operations. Only 2% of the result was determined by market timing.

On the one hand, this means that still remains the chance to beat the market with both the choice of individual securities (fundamental analysis) and the choice of time to enter and exit the market (technical analysis). On the other hand, it remains only within 4% of the impact on the result for the “fundamentalists” and within 2% of the impact on the result for the “techies”. And the most important thing that affects your result in the market (with a 94-percent-degree of influence) is not the right choice of operations time and not choosing the right specific stocks, but the proper distribution of assets into groups in your investment portfolio. That is, what is called Asset Allocation.

The published work caused a stir because it questioned the usefulness of Wall Street analysts and managers earning high salaries. After all, brokers and managers take money from customers, claiming that it is their analysts, managers and other gurus who know best when it comes to entering and exiting the market, and which papers are better to choose? Suddenly it turned out that the money is taken for the fact that minimally affects the result. Wall Street ‘inhabitants’ tried to argue with the academic world, however numerous repeated studies (including independent ones) confirmed the correctness of Brinson and the company’s conclusions. Now the validity of their conclusions is no longer questioned by anyone. However, this does not prevent representatives of the investment industry from further cutting the money from those who have no idea about the results of these studies.

I would like to emphasize: the study was related to the state the US market was more than 30 years ago. Since then, the markets have made a lot of progress in terms of their effectiveness.

But here is the problem. There are successful speculators (there are very few of them because the majority loses, but there are still successful speculators). There are successful active investors. But the problem is that for the overwhelming majority of people entering the markets and not trying to make financial market their main occupation, but simply willing to increase their savings, these approaches just do not fit. Why? First of all, because they require profound knowledge and experience. You will not become either a successful speculator, or a successful active investor in a week, month, or even six months. This is a long way of gathering knowledge, experience, taking hard knocks and very often losing money.

But portfolio (passive) investments imply the sufficiency of minimum knowledge and minimum experience. I will impudently say that some weeks of the evening webinars, which will be held in September, are going to be enough to correctly form the investment portfolio both at the moment and adjust it in the future.

Jeremy Stone Cryptocurrency Read 7min

Jeremy Stone Investments Read 11min

Jeremy Stone Cryptocurrency Read 8min

Jeremy Stone Cryptocurrency Read 5min

Musqogees Tech Limited 41, Propylaion street RITA COURT 50 4th Floor, Off.401 1048 Nicosia, Cyprus

+357 95 910654

info@musqogee.com